The Essence of Munger's 50 Years Reading Barron's: Compressed Time and Abandoned Free Will

Charlie's wisdom enlightens a generation of investors

In recent years, there have been numerous anecdotes about Charlie Munger, and two of the most memorable ones stand out.

Firstly, Munger voluntarily disclosed that he purchased shares of Shanghai Airport through Li Lu. The second involves Munger revealing that, after reading Barron's for 50 years, he stumbled upon an investment opportunity, earning nearly $80 million.

The company in question is an automobile parts supplier producing Monroe shock absorbers. The stock was priced at just $1, with its junk bond also priced at $35, carrying an 11.375% interest rate. Munger, upon reading an article in Barron's highlighting the stock's inexpensiveness, decided to invest in its junk bonds. As the junk bonds received interest payments from the company, yielding over 30%, their value surged to $107. Subsequently, the company redeemed the bonds, and its stock price rose from $1 to $40. Munger sold his shares at $15.

Munger achieved a 15x return on this stock investment, taking roughly two to three years. However, the decision to invest in this stock took only about an hour and a half, thanks to Munger's expertise in the automotive industry. Munger stated that his knowledge of the stickiness of the secondary market for cars and the need to replace Monroe shock absorbers in used cars made it clear to him that the stock was undeniably cheap. Despite uncertainties about the investment's profitability at the time, Munger deduced from the $35 price of the company's bonds that people were particularly afraid of the company going bankrupt. He considered this investment a "cigar butt" type, akin to picking up discarded but still valuable opportunities.

When asked by an investor about the story, Munger remarked, "Do you think what I just told you is useful for you? Probably not... You can't do what I do, and I can't help it. I don't find many opportunities, and the opportunities I find are not easy to come by. But once I find them, I don't hesitate."

This story, though familiar to many, may not be viewed from Munger's perspective by everyone. In this case, Munger's investment approach appears to be a mix of bonds and stocks.

Why did Munger choose to buy bonds when he could have bought all stocks? This requires a brief discussion of how Munger and Buffett perceive assets.

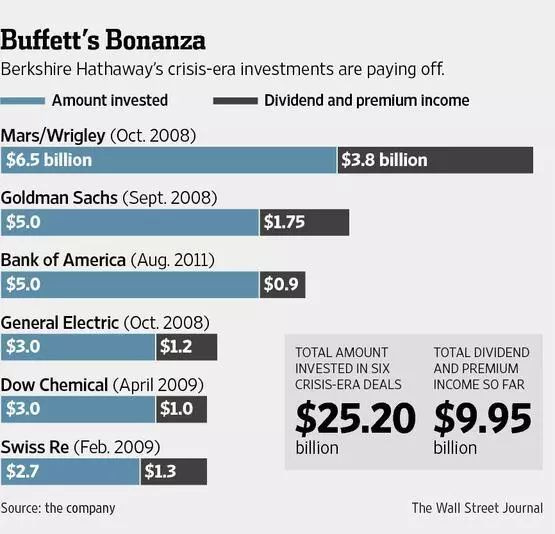

As known, Buffett likes to compare stock dividends with risk-free government bonds. In many investments, Buffett prefers low-risk bonds or convertible bonds. For example, in 2008, he invested in Dow Chemical and Goldman Sachs through convertible bonds. Both companies eventually found the financing cost too high and promptly ended these bonds at maturity, converting them into common stocks.

Now, let's think about Munger's case. He knew that the business had high stickiness, and the likelihood of customers abandoning it was low. However, the market investors believed that the company might go bankrupt. Consequently, even the junk bonds of the company were sold at an unbelievably cheap price. This means that the possibility of the junk bond interest being repaid was very high because the business still had a very high chance of survival. In other words, Munger preferred to see this opportunity as a "bond" rather than "equity."

Its certainty had reached the standard of a "bond," but the potential return had reached the standard of a "growth stock." This kind of opportunity is rare.

Recalling, I also had a similar opportunity, but at that time, my abilities and experience were insufficient, leading to me not seizing the opportunity that I should have.

In 2015-2016, oil prices plummeted, and Middle Eastern countries such as Saudi Arabia increased production to counter the threat of U.S. shale oil. Eventually, oil prices plummeted to a low, approaching around $30 per barrel. Canada, as a major oil-producing country, suffered a severe economic blow during this period.

I was not particularly interested in oil companies, even Suncor, Canada's largest oil company. What caught my interest the most was Canadian banks.

With the plummeting oil prices, Canada's employment rate also declined, the economy was bleak, and naturally, the banks' business declined. Worse still, many Canadian banks had loans related to the oil industry. The market began to worry that if oil prices remained low for an extended period, many loans would turn into bad debts. Consequently, Canadian bank stocks were being sold off.

The two largest banks in Canada, Bank of Montreal and Royal Bank of Canada, both reached new lows in January 2016. Canada's financial environment, relative to the United States, was relatively less active, with large banks essentially monopolizing the market. The overall financial system was conservative, and the percentage of loans to oil companies was not particularly high, not enough to threaten the banks' operations.

Although I had no idea about the future of oil prices at that time—whether they would remain at new lows or rebound—I knew that investing in oil companies, especially drilling companies, carried significant risks. It was at this time that the preferred shares issued by Bank of Montreal and Royal Bank of Canada caught my attention.

At that time, the prices of many publicly traded preferred shares plummeted, similar to the lowest point in the chart above. Taking the example of the preferred share mentioned earlier, it was around CAD 21.9 per share, providing approximately a 5.5% dividend yield. There were many such preferred shares to choose from, and investors at that time only needed to consider purchasing ones with better liquidity. If I had bought a substantial amount and held them until 2019, I could have enjoyed over 5.5% in annual dividends, along with an additional 10% from the rebound in preferred shares. Over three years, the average annual return would have been around 8.5%. If I had adopted a strategy of half stocks and half preferred shares, the return would have been even higher.

The return on this opportunity is naturally not as significant as Munger's discovery, but you probably understand my point by now. This wasn't the first time I considered a problem from the perspective of "bonds," but it was the first time I realized that using the "bond" approach could capture many opportunities that I couldn't judge at all. (Similar examples include Berkshire recently buying shares of Red Hat just to obtain the arbitrage premium of IBM acquiring Red Hat.)

A similar example occurred with Fox. After Disney announced the acquisition of Fox, Baupost, a fund operated by Seth Klarman, the author of "Margin of Safety," purchased a large number of Fox shares, accounting for 1/5 of its total position, making it the fund's largest holding. With the acquisition case about to be settled in a few days, looking back, this investment naturally proved to be very profitable, with a "margin of safety" quite high. I won't go into the details of Disney's acquisition of Fox here.

Returning to Munger, he bought shares of Shanghai Airport through Li Lu and was very proud of this asset. During a TV interview, he actively revealed that he believed buying shares of one of China's major airports would definitely not result in a loss.

In reality, Munger's view of Shanghai Airport is likely more similar to a bond. This is not difficult to judge. Firstly, the asset category of Shanghai Airport means there is no direct competition. The biggest fundamental is not the airport itself but the geographical location of the airport.

Shanghai's unique geographical advantage is reflected in the financial reports. Shanghai has the highest international transit passenger volume among Chinese airports and is still expanding. At the same time, Shanghai is also one of East Asia's most important international financial centers, one of the important ports in East Asia, and one of the important tourist destinations (Disneyland). From these perspectives, Shanghai Airport appears more like a bond or bond fund than a stock.

Betting on Shanghai Airport is, on a larger scale, a bet on China's future. Perhaps the process will have some twists and turns, but who cares? If this is a bond, it is not suitable for short-term buying and selling.

Li Lu probably bought Shanghai Airport for around 20 yuan, and now he has approximately tripled his return. With the rapid growth of Shanghai Airport's non-aviation business, it can be said that he picked up a big bargain.

After discussing so many cases, the key point I want to make is: when you learn to think about assets from the perspective of interest and bonds, your perception of time will change, and your perception of time will be compressed as you look at things from different angles.

It's like an athlete holding their breath, feeling the moment of kicking the goal. In that moment, their perception of time is "compressed," and even though it's the same second, the athlete feels the time process in that second is much longer than the casual second we experience in our daily lives.

Is it possible to amplify this ability to perceive time through contemplation? For example, compressing 50 years of experience into half an hour and then going all in on a highly certain opportunity? Yes, Munger did it.

The advantages of looking at problems this way are naturally very obvious, especially for those who are impatient to know the results. Taking Shanghai Airport as an example, if I approach it with a stock mentality, I would inevitably evaluate the ups and downs every quarter, assess non-aviation business from a growth stock perspective, and judge when to buy and sell based on the overall Chinese economy.

As I mentioned in the first article on the Wechat public account, the movie "Arrival," in the investment philosophy, if you already know the beginning, process, and end, would you still look at Shanghai Airport like I described above? Probably not.

Munger did it, but he said it's meaningless for most people. For me, I think his implicit meaning is: the cost of doing this is too high.

Suppose we are like the aliens in the movie "Arrival", or our thinking has reached the heights of Munger. What kind of price might we have to pay?

You constantly pursue the truth, discover the essence of things, and are generally correct in judging vague futures. In such a situation, you naturally have a better view of assets, especially their long-term performance.

We know that predicting the future with free will is impossible; it's a gift to humanity because we can predict what we'll do next second and accomplish it. But we must follow this fixed will.

The same logic applies to investment. If you know the approximate future, where China and the United States will continue to lead in the second half of the 21st century, with occasional conflicts but nothing serious, Shanghai becoming one of the most important cities in East Asia, surpassing Tokyo and Singapore, would you still care about the quarterly fluctuations of Shanghai Airport's stock price? If you can really see this future, you probably won't care about quarterly fluctuations. According to Fermat's Law, when you see the beginning, process, and end of the entire event, you will have to choose the "shortest, most labor-saving, and most efficient" path (holding Shanghai Airport for a long time is the most efficient path).

Why would you do this? Because if you don't choose this path, you violate the future you see, actively choose to restore free will, and you will also lose the ability to see the fuzzy future. (At least you will become hesitant, not firm enough, and your vision of the future is not certain enough.)

Stepping back, will the results really change due to your personal buying and selling? Does your existence have a significant relationship with whether China will continue to prosper and develop? I'm afraid these macro results will eventually inevitably develop to where they should be, that is, fatalism or purposeism. If this outcome is already destined, will you stand by or participate in it?

Looking at assets with the mindset of "bonds" helps compress your perception of investment time, and giving up free will (at least in investment) helps you judge high probability events.

What is the cost then?

The cost is not just sacrificing time and effort. Living a life where you "compress time" means you will likely have to sacrifice some "seven emotions and six desires."

You will lose some of the pleasures that ordinary people with free will can enjoy.

This kind of sacrifice seems to be a necessary condition for obtaining higher-dimensional thinking, at least from various literary descriptions. For investors, is the most important result really the most important? Or is the process more important? Suppose you can see the beginning, process, and end, does making money seem to no longer be a singular purpose?

It's like Munger didn't need to make that $80 million for a living. He read Barron's, saw an opportunity, bought and held, made a profit, and ultimately handed it over to Li Lu to invest in more valuable assets. This whole event feels like it's full of a sense of purpose.

Perhaps someone will ask, if it's not for love, how many people would be willing to bear such a cost? I would like to ask in return, if it's not actively giving up some degree of free will, relying solely on the passion of hot blood, can one really do one thing for a lifetime?